IN THIS LESSON

A practical look at how AI works, and what limitations it currently has.

Despite what people might have you believe, Modern AI is not a new idea. Slowly in the background, one process at a time, led us to where we are at now. However, I am not going to bore you with the details, you can get the other course if you want a breakdown on how all of this works. Instead, I am going to give you an understanding that will help you practically use ai today. It is quite likely that the details of what we are using now will change, but these practical tips will still be relevant.

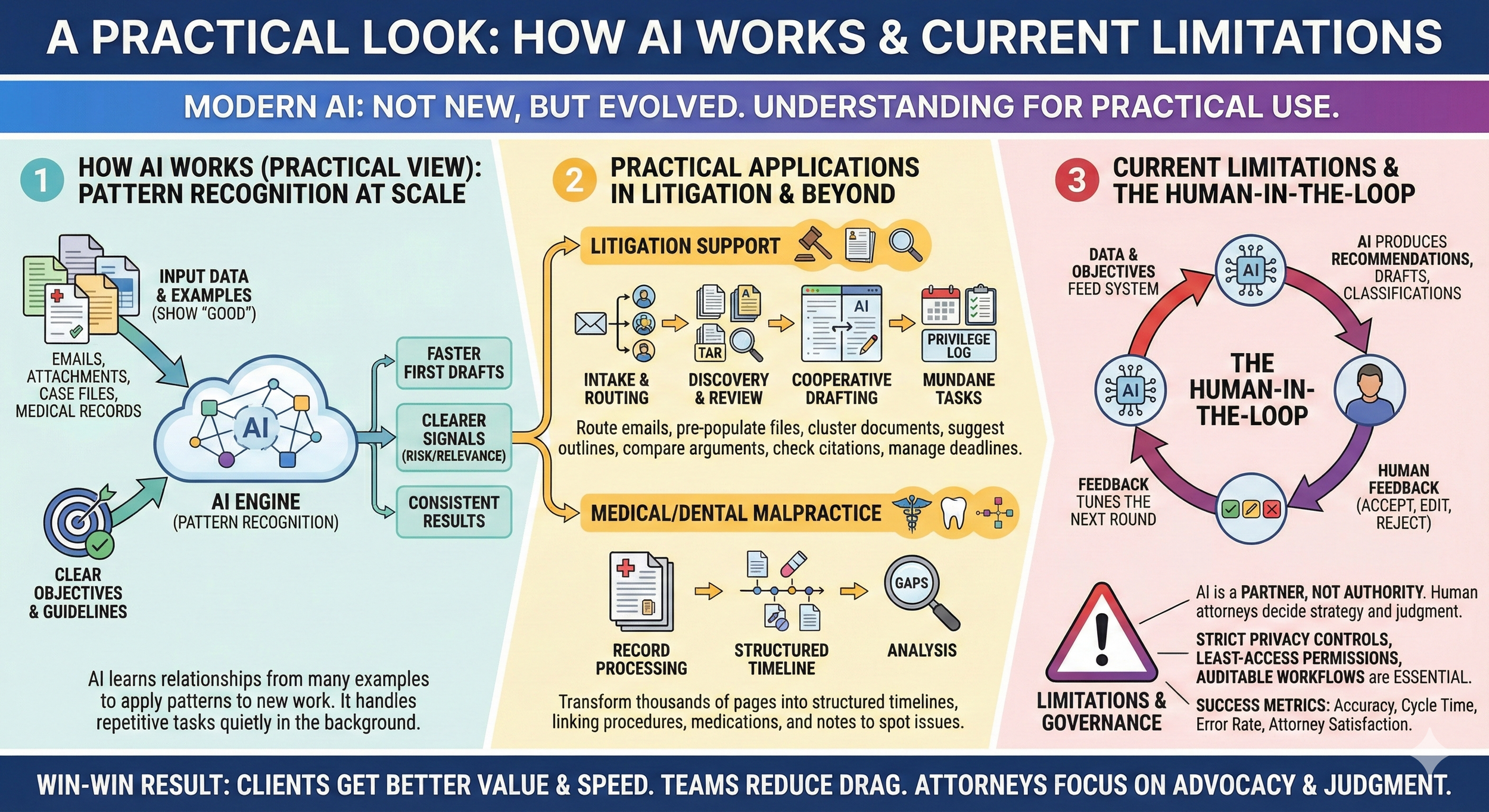

AI, in practical terms, is pattern recognition at scale: we show it many examples of what “good” looks like, it learns the relationships that reliably produce those results, and then it applies those patterns to new work so teams get faster, more consistent first drafts and clearer signals about risk.

In a litigation setting, that means AI can quietly handle the repetitive but essential tasks while attorneys stay focused on strategy and judgment. Intake systems, for instance, can read new matter emails and attachments, route them to the right teams, and pre‑populate case files with parties, dates, and venues—flagging potential conflicts or missing authorizations without slowing anyone down.

During discovery, technology‑assisted review can cluster similar documents, de‑duplicate threads, and bubble up likely relevant materials, while a human reviewer curates the final productions and privilege calls. For medical or dental malpractice matters, AI can transform thousands of pages of records into a structured timeline—linking procedures, medications, and provider notes—so counsel can quickly spot inconsistencies, gaps in care, or causal chains worth investigating.

As cases progress, AI becomes a cooperative drafting partner rather than an authority. It can assemble a first‑pass deposition outline from pleadings and prior statements, suggest follow‑up questions based on inconsistencies across witness declarations, and create exhibit lists with auto‑generated descriptions that match the court’s formatting preferences.

For motion practice, it can compare our argument to prior filings, highlight outlier facts, and propose counter‑arguments we should be ready to address—always with attorneys deciding what stands. Citation tools can check quotations against the record, confirm pincites, and warn when an authority has been negatively treated. Even mundane but vital tasks—maintaining a privilege log, updating a chronology after new productions, or syncing deadlines from a case management order—benefit from AI’s ability to standardize and monitor details in the background.

The goal is a steady, human‑in‑the‑loop loop: data and clear objectives feed the system; it produces recommendations, drafts, or classifications; and our feedback (accept, edit, reject) tunes the next round. Success is measured in concrete terms—accuracy, cycle time, error rate, and attorney satisfaction—and governed by strict privacy controls, least‑access permissions, and auditable workflows that preserve chain‑of‑custody and privilege. Done right, AI creates a win‑win: clients get faster, clearer work product and better value; teams reduce fatigue and administrative drag; and attorneys keep their attention on advocacy, negotiation, and judgment—the parts of litigation where human expertise remains irreplaceable.